“A caption: some kind of meteorite or alien visitation has led to the creation of a miracle: the Zone. Troops were sent in and never returned. It was surrounded by barbed wire and a police cordon.”

—Zona, Geoff Dyer

The ruins of the Union Carbide pesticide factory lie in the very center of India, in the state of Madhya Pradesh, which means Middle State. There, in the capital city of Bhopal, inside the old city that sits across a lake from the new city, inside the crumbling but imposing fortress gates and beyond the twisting medieval alleyways and public squares, past makeshift shacks, scrubland, and slime-filled canals, surrounded by a boundary wall and guarded by a contingent of policemen, is the site of the worst industrial disaster in the history of the world. But for all that, the factory is not inaccessible. It can be visited, with the correct permit. The walls surrounding it are full of breaches. There are slums right outside the factory site, from which children sneak in to play cricket. Cattle wander in to graze, making their way around discarded white sacks of pesticide, twisted pipes, and rusting metal parts. The blackened towers are visible from a distance.

There was a proposal, once, to turn the site into something else, into a national park that would include a memorial, a tourist center, a “craft village,” a technology park, and an amusement park. But three decades have passed since the disaster that began late at night on December 2, 1984, and the guarded, abandoned factory site is just that, a guarded (but regularly breached), abandoned site, a place where anything could have happened and maybe did happen.

For the people of Old Bhopal who woke up on the night of December 2, finding it difficult to breathe, their eyes burning, it was as if some great, unknown evil had taken place. They did not think of the factory as the source of their distress, not unless they had worked there and knew of its troubles or had been among those active in protesting its location in their midst. Most people thought there was a fire in a chili warehouse somewhere, sending clouds of toxic fumes their way—and because burning chilies are sometimes used to chase off evil spirits, this seemed to be a case of an exorcism gone out of control, the protecting magic indistinguishable from the possessing evil.

But the source of this particular evil was, in fact, the factory. An accident there had sent forty metric tons of methyl isocyanate (MIC), a lethal chemical, into a runaway reaction that released a toxic gas. The gas filled the night air of Old Bhopal and entered into people’s bloodstreams, where it then dissolved into hydrocyanic acid, attacking the lungs, respiratory tracts, kidneys, liver, and brain. In order to get away from the choking, burning air, people abandoned their houses and tenements. They ran away from the slums, out of Old Bhopal, across the lake and the hills that divide New Bhopal from Old Bhopal and that would keep the city’s wealthier residents relatively safe even as the poor choked on the fumes. They poured into the new city, into the railway station, some dying in the stampede, others succumbing to the fumes. So many people died that mass cremations and burials took place, bodies piled one on top of another. Corpses were loaded onto trucks and hastily driven out of the city.

It is possible to say, in the case of the 1986 Chernobyl disaster, that three people died immediately at the site of the explosions and that twenty-eight more died from acute radiation syndrome within the year. It is also possible to say, with regard to the accident at Fukushima in 2011, that so far there have been no radiation-related deaths. But it is not possible to say, in spite of all those corpses and the many years that have passed, exactly how many people died in Bhopal from the MIC leak. The Indian government initially claimed extremely modest figures for deaths and injuries, but there are estimates, based partly on the number of funeral shrouds sold the day after the accident, that at least 3,000 people died within the first twenty-four hours. After that, the assessment of fatalities fluctuates wildly, but it’s likely that more than 20,000 people have died in the past thirty years from effects of the gas.[*]

The fallout of the leak extends well beyond even that, with perhaps half a million survivors impaired with breathing difficulties, vision problems, spells of unconsciousness, and psychological disorders. Women suffer a high rate of miscarriages, and children are prone to birth defects. The abandoned factory overruns its boundary walls even if it appears to be sequestered; chemicals stored on site or dumped into pits seep into the groundwater and make their way into the tube wells and taps of surrounding slums. Today, thirty years after the events of December 2 and 3, 1984, the factory continues to pulsate with its evil magic.

Safety Last

Union Carbide, founded in 1917 and since 2001 a wholly owned subsidiary of the Dow Chemical Company, set up its Bhopal factory in 1969. But it had established its presence in India long before then. Although the Indian economy was driven at the time by autarkic principles that limited foreign control of Indian companies, Union Carbide had found a way of operating freely and profitably within such notional restrictions. Like Nestlé and Unilever,[**] other giant multinationals, it concentrated on the kinds of things needed by a developing country, packed its board of directors and senior management with Indian industrialists and the relatives of important politicians, and emphasized its own, somewhat spurious, Indianness.

In reality, it was one of the largest chemical companies in the United States, with corporate headquarters in New York (later moved to Danbury, Connecticut) and an Asia head office in Hong Kong. The 50.9 percent stock it held in Union Carbide India Limited (UCIL), its Indian subsidiary, was a controlling stake, and senior positions at UCIL were filled on instructions from Hong Kong or New York. Although UCIL’s most profitable group was the battery division, with a virtual monopoly in India, the factory in Bhopal was set up to manufacture a product aimed at farmers rather than urban households. This was the pesticide carbaryl, marketed under the brand name Sevin. Another pesticide, Temik, was also made at the factory, in smaller quantities, but Union Carbide’s promise of food for the masses was carried largely by Sevin, a white powder sold in paper bags of 25 kilos each.

Sevin came from an industry with a macabre past. Pesticides originated in chemical weapons, and German firms, with their expertise in poisoning British and French soldiers during World War I, dominated the business in the beginning. One such firm was BASF, part of World War II’s notorious IG Farben group; the group ran a unit called IG Auschwitz and produced Zyklon B, a gas pumped into the chambers at the death camps.[***] Two decades later, the Dow Chemical Company manufactured napalm so that the Vietnamese could be killed cheaply and easily in large numbers. And agricultural pesticides themselves had unintended consequences. Rachel Carson’s book Silent Spring, published in 1962, showed how DDT, at the time a popular pesticide—and one still widely used in India—is a nonbiodegradable toxin that remains present in fish and wildlife and even works its way into human breast milk.

Maybe this history has little to do with the coming of Union Carbide to Bhopal. No doubt, there was some Indian demand for pesticides, which, along with chemical fertilizers, were considered to be the key ingredients in India’s so-called Green Revolution, allowing food production to keep pace with a growing population. That technology has since been called into question as unsafe and unsustainable for both the land and the people who farm it, but the Indian government in the sixties would have had few doubts about the seemingly advanced Western science represented by Sevin.

For the people of Old Bhopal who woke up that night, it was as if some great, unknown evil had taken place.

Union Carbide, in any case, promoted Sevin as a safer alternative to DDT: less dangerous for humans, biodegradable, and effective against a wide range of pests. It did not publicize the fact that its process for manufacturing Sevin required a number of lethal chemicals, including phosgene (one of the gases used during the trench warfare of World War I, along with mustard gas and chlorine)[****] and MIC. Made by combining phosgene and monomethylamine, MIC is a highly volatile chemical; it reacts with water and other substances and needs to be kept cool to prevent unwanted reactions. The only other Union Carbide factory that produced MIC was located in Institute, West Virginia—most chemical companies avoided MIC and preferred a different, more expensive, way of producing pesticides similar to Sevin—and Institute had had its share of accidents, especially leaks in the MIC unit.

The Bhopal factory started small, with a “formulation” unit that mixed already prepared chemicals to produce Sevin. The mixing procedure was fairly basic, and there were many such formulation factories in India. But the idea, from the very beginning, had been for Union Carbide to create a “technical” unit, one in which advanced proprietary technologies would be used to manufacture the pesticides from scratch. The Indian government, according to Union Carbide, wanted the technology to be imported into the country, which is probably true. Government leaders would have seen it as a step toward becoming a developed economy, boosting both agriculture and industry. Union Carbide, too, was interested in manufacturing locally. It had been exporting Sevin to India for some years; now it could eliminate international shipping expenses, take advantage of lower labor costs, and be centrally located in a market it perceived as the largest in the world after China, with 550 million acres under cultivation and a population of 560 million.

After initially importing MIC directly from the West Virginia factory, the Bhopal factory installed its own MIC unit in 1979. The completed setup, in anticipation of heavy demand for Sevin, had an annual production capacity of 5,000 metric tons. But the market for Sevin turned out to be far smaller than expected, with Indian farmers unable to afford it and preferring indigenous products, and so, through the early 1980s, the Bhopal factory operated at half its production capacity.

The Contamination of Everything

There had always been shortcuts in safety procedures.[*****] Union Carbide built the factory in a densely populated urban area over protests from local people and legislators, and chose to store large quantities of MIC there even though electricity in the area was undependable and temperatures regularly crossed 110 Fahrenheit in the summer. When there were mechanical failures, as in the alpha-naphthol unit, the company directed poorly paid contract workers to crush the alpha-naphthol with hammers and carry it to the reactor; the workers were unaware throughout of their exposure to toxic vapors. And once the market failed to match production capacity, other safety measures were eliminated, seemingly to save costs in a factory that was nowhere as profitable as had been originally envisioned.

An inspection team visiting from the United States in 1982 noted several safety problems, and one of the visiting inspectors sent a telex stating that they “had to destroy 1.8 MT of MIC due to water contamination/trimerization.” A supervisor and one of the operators got injured the same year during a chemical spill. Some of the technicians skilled in chemistry, hearing rumors that the factory would be closed down, left for other jobs; a number of them went to Iraq, then fighting a war with Iran. Management staff began leaving too, replaced by people from UCIL’s profitable and influential battery division, who, it was said, had little knowledge of pesticide factories. By 1983 the World Agricultural Business Team at Union Carbide’s headquarters in New York had decided to sell the Bhopal factory. If the company was unable to dispose of it by the end of the next fiscal year, the factory would be closed down and the costs written off.

This meant that most of the safety devices at the factory, especially those intended to contain MIC, were inoperative by the time of the disaster. The production of MIC had halted, but large amounts of the chemical were stored in three underground tanks. The cooling system, which could slow down unexpected reactions, had been shut off to cut costs; the scrubber unit that neutralized escaping chemicals wasn’t functioning; the flare tower at the very top, meant to burn off toxic vapors if all else failed, had been dismantled for repairs. All that was left was a windsock, which allowed the workers on the night of the disaster to see the direction of the wind, heading southeast toward the crowded, poor quarters of Chola, J.P. Nagar, and the railway station.

Some of this can still be seen when one visits the factory, as I did ten years ago. Time seems half-suspended, the night of the accident preserved in the fashion of some permanently stopped Hiroshima clock. The factory sprawls on its sixty-two-acre grounds, the blackened pipes and rusting metal parts evoking something that could be either the remnants of a nineteenth-century industrialism or an utterly alien technology. The shelves and racks in the quality control building still hold bottles of chemicals, the labels faded and covered in thick layers of dust. There are broken, small-scale models of the alpha-naphthol, MIC, and Sevin units in the control room, eerie echoes of the looming structures visible through the dense vegetation.

The cooling system, which could slow down unexpected reactions, had been shut off to cut costs.

At the Sevin unit, light reflects off the silver gleam of strings of mercury drops, and the blackish-brown dirt around a collapsed chute has a thick, sweet, chemical odor with just a hint of putrefying animal flesh. In the MIC unit, lengths of a black hose are visible, perhaps left over from the night of the accident, when a hose was apparently used to flush out solid impurities choking a set of pipes. The washing was a routine operation, and the water should have come out through some vents; instead, it was blocked by the impurities and flowed in the direction of 610, one of three underground tanks used to store MIC. When water entered 610, it reacted with the MIC, building up a flow of gases that retraced the route to the MIC unit. With the cooling system shut down, the reaction in 610 was fast, and without the scrubber and flare tower, the journey of the gases was unimpeded.

The tank itself, a giant black cylinder with a spout, lies on the ground, long removed from its underground housing. Around it, it can sometimes seem as if a cycle of renewal is in progress: creepers and shrubs making their way back into the buildings; red, orange, and purple bursts of flowers; bird eggs in the rubble of the administrative office; perhaps a snake lurking near the formulation shed. But the flowers and snakes exist not in paradise but in a modern wasteland, where the sheds contain sacks and drums stuffed with Sevin and naphthol residue. Along the northern wall, next to the slum of Atal-Ayub Nagar, there are piles of rubbish, with white Sevin sacks strewn on the ground. In the concrete tanks where liquid waste was dumped, a dark crust has formed on the surface, shot through with yellow streaks like frozen fat in a meat curry.

The damage, of course, extends well beyond the boundary walls. Samples tested separately by Greenpeace, the Boston-based Citizens’ Environmental Laboratory, and the People’s Science Institute, an independent Indian organization, have shown the presence of toxins in the drinking water of nearby slums, and farmland in the area remains unusable.

The Butcher’s Bill

Those affected by the poisons make do the best they can. Protesters have caused the water pumps in slums like Atal-Ayub Nagar to be painted red and marked as dangerous. Municipal tankers deliver water at irregular intervals to a few black plastic drums placed in the slums by the government. There is a hospital for the afflicted, an expensive auto-rickshaw ride away from the old city, and a cheap, shabby housing estate known as the Gas Widows’ Rehabilitation Colony. Within this grudging setup, people go on: the woman with the twisted limbs, the man who lost his family, the boy who turned schizophrenic, the girl with the unusually large head. For those who are part of the dwindling original group affected directly by the MIC leak, their accounts are composed of memory fragments and body parts, yellowed paper and shabby surroundings, eagerness and hopelessness.

If there is any sustenance, it is provided by the victims themselves and the two local activist organizations that have struggled in their cause. In the immediate aftermath of the accident, concerned citizens and activist groups banded together in a loose coalition called the Morcha to provide help to the afflicted. When the Morcha broke up, two principal organizations emerged, the Bhopal Gas Peedit Mahila Udyog Sangathan, led by Abdul Jabbar, and the Bhopal Group for Information and Action, run by Satinath Sarangi. Without these two organizations, the first a feisty trade-union-style outfit with deep local roots, the other excellent at disseminating information on the Internet and liaising with foreign activists and groups, the victims would have been entirely at the mercy of the Indian government and Union Carbide.

The government quickly declared all the victims “wards” of the Indian state. This was done, it was said, to protect them from the predatory American lawyers hanging around Bhopal, asking people to place their thumbprints on documents in exchange for promises of compensation money. In hindsight, it’s hard not to think they might have been better off as clients of those pinstriped hucksters than as neglected wards of a callous state.

The Indian government, unilaterally representing the victims in its suit against Union Carbide, tried to have a trial in the United States, where there were no upper limits to compensation. Union Carbide asked for the case to be heard in India, pleading the excellence of Indian courts. It won the argument, and the case went to trial in India, where in 1989, five years after the accident, the government decided to accept an out-of-court settlement of $470 million in compensation from Union Carbide. For Union Carbide, and for the Dow Chemical Corporation, which later acquired Union Carbide, this settled the matter in perpetuity.

Dow has insisted that it has no connection to Bhopal at all, a position that has not, however, stopped it from buying up the domain bhopal.com to present its one-sided story. It insists that the average victim should have received $500, which, as one of its PR flacks argued in 2002, is “plenty good for an Indian.”[******] The Indian government distributed that plenty-good money at a glacial pace, claiming in 2006 that it had finally finished the payouts.

But the leak also prompted a criminal case, and that case has yet to be resolved. Union Carbide, which at first described MIC as no more dangerous than tear gas, began its search for a scapegoat by blaming Sikh terrorists (there was a Sikh secessionist movement in India at the time). It then changed course to argue, based on a study authored by an Indian engineer working for the management firm Arthur D. Little, that the factory was sabotaged by an unidentified, disgruntled worker. This study was based on the argument that there is a “reflexive tendency” among workers to lie, on the year-old testimony of a single engineer at the factory, and on a statement by a twelve-year-old canteen boy that the workers had looked tense that night.

In India, the Central Bureau of Investigation took charge of the factory after the accident, considering it material evidence in the ongoing criminal case. But the legal ownership of the factory is another matter. In 1991 the Indian Supreme Court, reviewing the original settlement of 1989, upheld the compensation amount of $470 million, although it struck down the clause guaranteeing Union Carbide and UCIL immunity from criminal proceedings. In 1992 Union Carbide announced that it would sell its 50.9 percent stake in UCIL and put $17 million of the proceeds into a trust aimed at building a hospital for accident survivors. A few days after this announcement, the chief judicial magistrate of Bhopal ordered the confiscation of the company’s remaining assets in India. In April 1994 the Supreme Court allowed Union Carbide to go ahead with the sale, and in November of that year the majority stake in UCIL was bought up by McLeod Russel India Limited, an Indian company owned by the B.M. Khaitan group. The Bhopal factory, in effect, belonged to the new owners, although it was technically still in possession of the CBI and the state government.

What all this corporate maneuvering really means is impossible to tell. In October 1997, when the Madhya Pradesh Pollution Control Board commissioned a report on toxins at the site, the factory still belonged to McLeod Russel (which had, since acquiring UCIL, changed the name to Eveready Industries India Limited). But in July 1998 EIIL turned over the lease to the government of Madhya Pradesh. The site remains, according to most accounts, contaminated.

Meanwhile, in spite of his professed faith in the excellence of Indian law, Union Carbide CEO Warren Anderson, who had flown to Bhopal after the accident, decided not to stay around for the criminal trial. A brief arrest, a bail of $2,000, and he was back in the United States, where he now lives a retired life in the Hamptons, playing golf. His status as a wanted man in India amounts to nothing, although Greenpeace activists or foreign journalists sometimes show up at his doorstep and try to elicit a response to the disaster.

Anderson isn’t Eichmann. In “Hunting Warren Anderson,” an investigative segment directed by John Firth and aired on Australia’s SBS TV, Anderson looks like just another aging corporate official. When the crew traces him to his house, he is merely a shadow glimpsed through a window, a tall man, perhaps leaning over a kitchen counter. Anderson doesn’t come out of the house in the film. Instead, it’s Mrs. Anderson who does the talking, an elderly woman at the wheel of a large car. They have a family party later that night, and it is uncatered. Her voice quivers in outrage as she tells the reporters standing in her driveway, “Get off his back.”

Come Back Now, Dow

Mrs. Anderson’s outrage is shared by many members of the Indian elite, who seem to feel that this business of talking about the dead and dying of Bhopal has gone on for far too long. The first decade of Indian response was that of the state’s great indifference toward the victims and even complicity with Union Carbide and its successors. That has now given way to the attitude among the upper classes that the victims and their supporters are holding back India’s inexorable progress. Basking in the profitable embrace of neoliberalism, the elite that loves to love U.S. corporations and loves to hate its poor has made significant efforts to make sure that Dow feels welcome and fully at home in India.

Led by Dow partners like Ratan Tata, a group of Indian industrialists, many of them luminaries of something called the India-U.S. CEO Forum, offered in 2007 to clean up the Bhopal factory if only the government would agree to let Dow operate in India without “legal liability.” This was meant to be a small footnote to the U.S.-India Civil Nuclear Agreement, but the Indian government, after a public outcry, eventually backed off from providing legal cover. Dow’s Indian dealings, meanwhile, remain mired in scandals, including bribes paid to Indian officials. In 2008 protestors successfully blocked construction of a Dow R&D plant in Chakhan, near Mumbai. But the machinations of Dow and its Indian compradors are part of a larger story. In India these days, there are fantasies of a hundred more Bhopals in the form of secrecy-shrouded nuclear plants and river-damming projects, of pharaonic, Ozymandian monuments rising from the valleys and the mountains. Against this, there are the small acts of resistance by a multitude that understands what the elites repeatedly get wrong: the evil of technologies meant to bring profits and power only to a few.

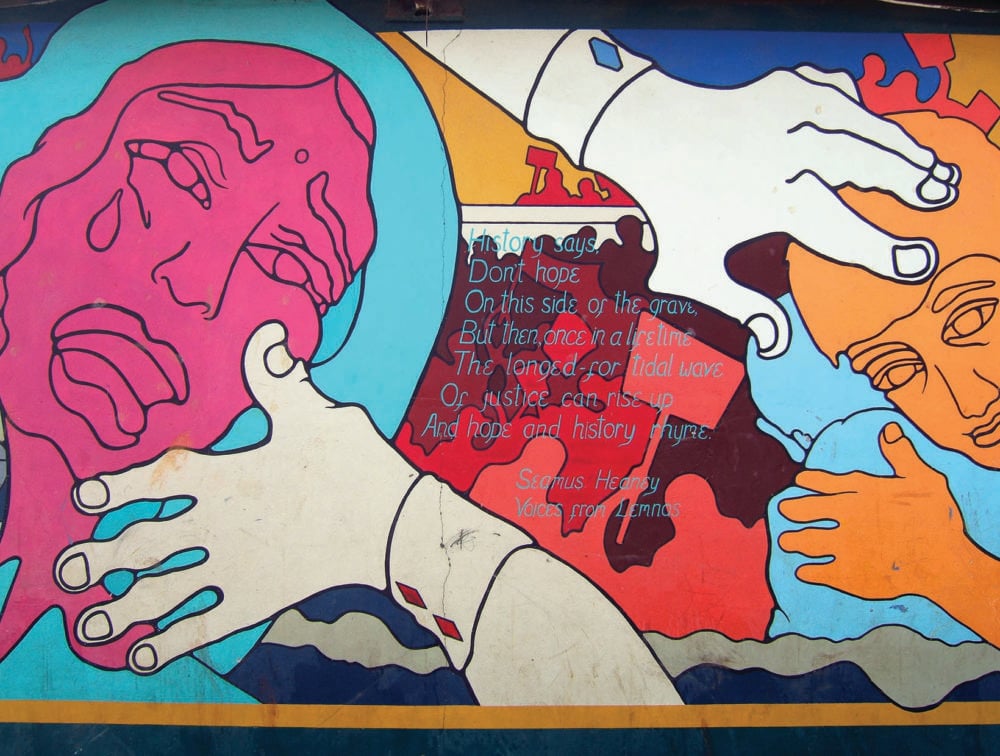

In front of the J.P. Nagar slum, there is a sculpture by the Dutch artist and Holocaust survivor Ruth Waterman. It has its back to the factory and faces the slum, a statue of a mother and a child made of plain concrete and raised on a small plinth, hastily erected while slum dwellers held back the police sent in to prevent it from going up. On the wall of the slum, talking back to the statue, is a scrawled slogan, black on plain brick, that says, “Hang Anderson.”

But truth be told, no one really wants to, should they get the chance, place a noose around the neck of a former CEO. The Anderson they want to hang is Union Carbide, Dow, the Indian government, the India-U.S. CEO Forum. The Anderson they want to hang is Ravana, the demon king sent up in flames when the festival of Navratri culminates in Dussehra. The Anderson they want to hang is the djinn who wafted across the rooftops of Bhopal that night, shrouded in toxic smoke. The Anderson they want to hang is Uncle Sam, the imperialist and plutocrat in his striped trousers and top hat. The Anderson they want to hang is an evil thing, a meteorite, an alien visitation.[*******]

[*] The usual range quoted is 3,000 to 4,000 within the first twenty-four hours; I have cited the lower end. According to Amnesty International, 7,000 people died “within days,” a total that climbed to 22,000 in the following years, with another 100,000 people subject to “chronic and debilitating illnesses.” The Bhopal Memorial Hospital and Research Centre, run by a trust established in the aftermath of the accident, estimates that 500,000 people suffered “agonizing injuries.” A report in the Guardian noted that the office of Bhopal’s medical commissioner “registered 22,149 directly related deaths up to December 1999.”

[**] Unilever, an Anglo-Dutch company, has its own toxic history in India; in 2001 it was caught dumping mercury in Kodaikanal, Tamil Nadu.

[***] BASF is still in business, and a leading union-buster; in the 1980s protests over conditions at one of its U.S. plants (in Louisiana’s “cancer alley”) ended in a five-year lockout.

[****] The poem “Dulce Et Decorum Est” by Wilfred Owen describes a WWI poison gas attack: “Gas! Gas! Quick, boys!—an ecstasy of fumbling,/Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time;/But someone still was yelling out and stumbling,/And flound’ring like a man in fire or lime . . . /Dim, through the misty panes and thick green light,/As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.” A woman I met in 2004 named Ghazala, who was twelve at the time of the Bhopal disaster and was blinded by it, described her experience of the fumes to me in a metaphor that was the obverse of Owen’s, of feeling “like a fish out of water.” But the experience, in essence, was the same—that of being unable to breathe.

[*****] According to researcher Bridget Hanna, the Bhopal factory was, from the beginning, less safe than the factory Union Carbide operated in West Virginia. In “Bhopal: Unending Disaster, Enduring Resistance,” Hanna writes: “Although UCC claims that its plant in Bhopal was built to the same safety specifications as its American facilities, when it was finally constructed there were at least eleven significant differences in safety and maintenance policies between the Bhopal factory and its sister facility in Institute, West Virginia. For example, the West Virginia plant had an emergency plan, computer monitoring, and used inert chloroform for cooling their MIC tanks. Bhopal had no emergency plan, no computer monitoring, and used brine, a substance that may dangerously react with MIC, for its cooling system. The Union Carbide Karamchari Sangh (Workers’ Union), a union of Bhopal workers that formed in the early 1980s, recognized the dangers at the factory but their agitation for safer conditions produced no changes.”

[******] Two years later, Dow representatives stated in a press release that they “wishe[d] to retract” the remark, the “poor phrasing” of which had “often come back to haunt” them. In the same release, Dow made it clear that while it has no plan to offer reparations to the Bhopal victims and “cannot and will not take responsibility” for the disaster (because “Dow’s sole and unique responsibility is to its shareholders”), a different public relations strategy is in place when it comes to its dealings with Americans. Dow “settled Union Carbide’s asbestos liabilities in the U.S.” and “paid U.S. $10 million to one family poisoned by a Dow pesticide,” according to the statement. “This is a mark of Dow’s corporate responsibility.”

[*******] [After this piece went to print, the New York Times reported for the first time that Warren Anderson had died in September 2014. The author of this piece reflected on that news in a piece for the Baffler blog, here. —Ed.]